|

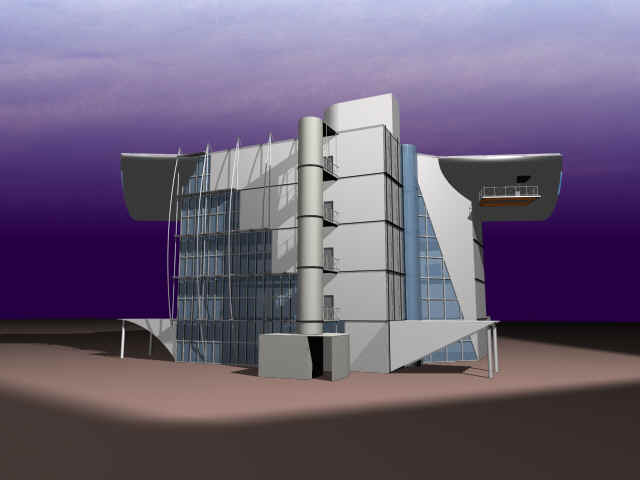

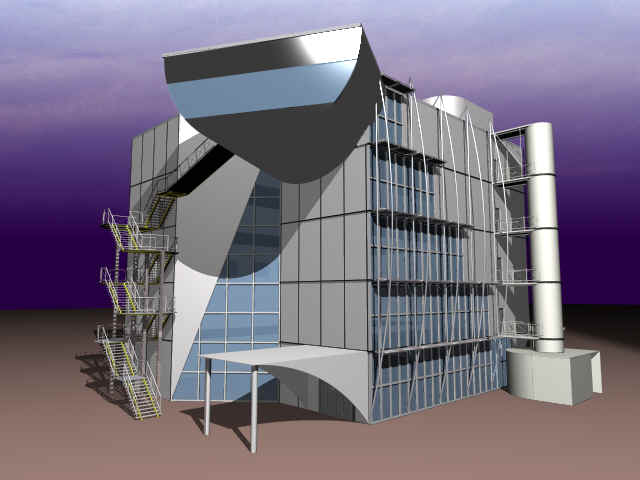

TOKYO INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY CENTENNIAL HALL |

|

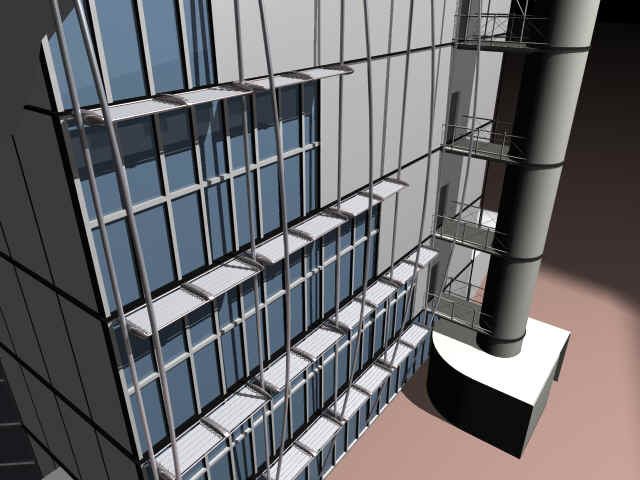

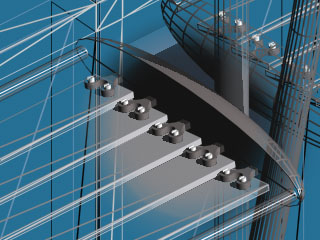

This project is taken from an existing building - Tokyo Institute of Technology Centennial Hall. The 3d model is drawn base on the floor plans, a few photo the elevation and the rest from part of my design. As the result this building does not look exactly similar. Mechanical shading devices are fixed on north and south facade (to reduce direct sunlight go into the building). The mechanical shading devices rotate accord with altitude of the sun. (Shading devices and building animations)

He is, by his own admission, a contrary man. In the days when the

Metabolists were proposing technologically oriented solutions, he took

an aestheticist stance. He avoided using Le Corbusier's name when it was

The

architect, long fascinated by the Apollo lunar landing module and the F-

14 jetfighter; first imagined a gleaming cylinder floating in space.

Ultimately, the cylinder-reduced to a haflcylinder came to be

supported on two wall slabs; nevertheless, under the right conditions it

seems suspended in mid-air.

The answer may be that Shinohara no longer needs to work solely with houses. Indeed, houses by their very nature may hamper the full expression of his emerging worldview. He began with a vision of a perfect, unitary world. His earliest houses, such as the Umbrella House (1962) and the House in White (1966), with their centralized schemes and large, sheltering roofs, were self-contained, ideal spaces. The additions to his oeuvre over the years record the gradual destruction and fragmentation of those spaces. Compare any one of the early works to the House Under High Voltage Lines (1982) or the House in Yokohama (1984), and one sees how a serene and predictable world has given way to a world with its full share of shocks and surprises, one that opens itself up, albeit in idiosyncratic ways, to the larger world.

Centennial Hall is located just inside the main gate to the campus of

the Tokyo Institute of Technology and accommodates a museum, social

facilities, and meeting rooms. A gleaming half-cylinder, clad in

stainless steel, penetrates a four-story block wrapped in aluminum and

glass. The formal elements of Centennial Hall are not knit tightly

together. Instead, they are juxtaposed as if by happenstance.

Inside, on the third floor the bottom of the half-cylinder cuts

diagonally across the ceiling of a lobby, a reception room, and a small

conference room, and to an observer the effect is startling, as if he

were looking up at the belly of an airliner that had crashed into a

conventional building. Shinohara intends the clash of completely

different scales, materials, and axes to generate what he calls

"random noise," which he believes to be the source of new

values, ideas, and points of view.

Centennial Hall is one of the most important Japanese buildings

of the 1980s, and together with the projects emerging from his atelier

represents a notable departure from his previous work. Over the years, Shinohara's preoccupation with houses has caused some observers, even ones who recognized his brilliance and originality to begrudge him unqualified praise. The foremost architects, it was implied, are those who excel in works at all sorts of scales and with all sorts of program requirements. The suggestion may or may not be valid, but soon the whole point as far as Kazuo Shinohara is concerned may become irrelevant. |